Summary

In a previous article we discussed the differences between the FDA and FTC agencies, and how, while pharmaceuticals are overseen by the FDA, nutraceuticals as ‘foodstuffs’ are largely regulated by the FTC. In this article we will explore how the nutraceutical regulations compare in the USA and abroad, asking how they are defined in each country, what licensing is needed, how this affects manufacturers, and what this indicates for the future of the market.

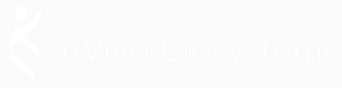

In 2010, the out of pocket spending on dietary supplements was a third of what people spent on prescription drugs, in 2012, 30% of Americans took more than four supplements a day, and in 2020 the USA market size was approximately USD $46 Billion (Zayets, 2019; Business Wire, 2021). Thus, dietary supplements are not only a large and growing market, but they are a part of people’s daily lives. In fact, the dietary supplement industry in the USA began when pharmaceutical companies marketed vitamins in magazines such as ‘Good Housekeeping’ and ‘Parent’s Magazine’, encouraging these products to be thought of as an important part of our daily lives to aid in proper development and resist illness (Zayets, 2019). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the global market for dietary supplements experienced a notable boost in sales, a testament to how readily consumers bought into this mentally [Figure 1].

Figure One. Supplement users in the USA who have altered their routine during COVID-19 (CRN, 2020).

Definitions of Nutraceuticals

As described in a previous article, in the USA nutraceuticals fall under the regulatory umbrella of ‘dietary supplements’, but while worldwide consumer demand for these products is robust there is no international agreement that outlines and defines these products. Rather, nutraceuticals’ regulations vary between countries, and are referred to many different ways: as Natural health products (Canada), health foods (China), herbal medicinal products (EU) dietary supplements (EU & USA), herbal products, plant-based nutrition, and nutraceuticals & ingredients.

What Licensing is needed?

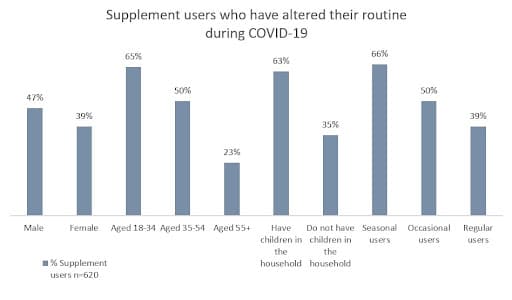

Due to the variation in nutraceutical regulations between countries, the process of getting a product to the consumer can look very different, and have a very different timeline depending on the country in which you are producing and/or selling your product in.

Figure Two. Nutraceutical distribution channel (Fiorito & Livatino, 2019).

USA

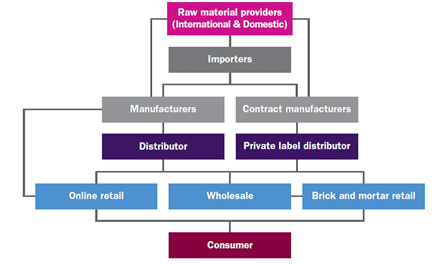

In the USA dietary supplements are regulated using a reactive approach (taking action against a product post-market when there are consumer complaints), rather than a proactive approach (such as pharmaceuticals which require premarket approval) [Figure 3]. Notably, while dietary supplements in the USA are required to comply with the CGMP (Current Good Manufacturing Practice Regulations), which specify operation processes that ensures the “identity, strength, quality, and purity” of products, the suppliers of materials are exempted (FDA, 2021) [Figure Three]. Consequently, critics, consumers, and regulators themselves, have voiced concern over the USA’s oversight, noting that the USA continues to have less stringent oversight for nutraceutical products compared to other countries. This being said, in 2021, the FDA/FTC issued more warnings to nutraceutical companies than they had in any year previously.

Figure Three. Safety & Efficacy required to bring Nutraceuticals ‘dietary supplements’ to market in the USA.

Canada

Like in the USA, in Canada nutraceuticals are not considered part of the pharmaceutical pipeline, however they are classified as a subclass of medicine and overseen by Health Canada (HC). This being said, Canada has stricter regulations than the USA, as ‘Natural Health Product’ manufacturers are required to obtain product license (covering dose, potency, ingredients, recommended use) and must show proof of good manufacturing practices, adverse reaction reporting, and evidence supporting health claims (clinical trial, published literature, or pharmacopeia) before gaining authorization to bring products to market. Canada still is less restrictive than the EU or China.

Canada is also currently developing a separate regulatory framework for ‘supplemented foods’ which they define as a product that is sold as a food but contains added vitamins, minerals, amino acids, herbal or bioactive ingredients.

European Union (EU)

Health products in the EU are considered to be strictly regulated – both by industry insiders and by the USA Congress which has recognized the EU’s level of regulations as a concern to supplement trade (CRS Report for Congress, 2005). Notably to the USA Congress, the EU has very defined guidelines surrounding the ingredients used in health products. This is an important difference between the USA and the EU’s approach to health product regulations, because, while suppliers of natural ingredients are exempt from regulations in the USA, in the EU compliance with their regulations is necessary if you want to supply natural ingredients to any health product manufacturer. That being said, while the EU has some overarching regulations, each member country has their own laws and regulations.

Since 2002, the EU has created a series of Food Supplement Directives which have created a legal and regulatory framework for food supplements – these include guidance on food labelling, use of additives, maximum levels for residues and contaminants, and general food safety/hygiene per the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP). Also, similar to the USA, the EU requires novel foods and food ingredients go through an approval process (however the EU’s ‘new ingredient’ regulations concern ingredients not on the market prior to 1997, whereas the USA considers new ingredients to be ingredients which weren’t on the market before 1994).

As previously noted, the EU faces the challenge of member states having their own views and approaches – this is particularly pertinent in products which are in the grey zone of being considered a food supplement versus a medicine. For instance, melatonin is prohibited in the Czech Republic despite it legally being acknowledged as a food supplement in other Member states.

Beyond the inter-country differences, legislation is made even more complex due to the constant re-evaluation and additions of regulations surrounding nutraceuticals. For instance, in 2006 the EU outlined the appropriate use of nutrition and health claims in the NHCR (nutrition and health claims regulation), and specified that such claims were required to go through a scientific assessment and verification by the European Food Safety Authority, however, by 2009 it was evident that the evaluation of all the claims would take a significant amount of time. Consequently, the vast majority of currently approved claims come from a consolidated list that was evaluated via published literature. Other applications, however, were placed on hold – such as health claims for botanicals (plants) which are still delayed. This has created a Schrodinger’s Cat situation as many EU member states allow botanicals to market using health claims even though these claims have not been scientifically assessed and risk managed.

China

There are two means of entry into the Chinese market: the ‘Traditional Trade’ route which are for products sold on Mainland China, and the ‘Cross-Border E-Commerce’ (CBEC) route which are for products sold in Hong Kong.

- Traditional Trade: all products sold on mainland China require pre-approval from China Food and Drugs Administration as well as ‘Blue Hat’ certification (registration based on scientific evidence that takes years to complete).

- Cross-Border E-Commerce: applicable to products being sold in Hong Kong. “Health foods” are extremely prevalent in Hong Kong, in fact, it is one of the fastest growing biotechnology and biomedical innovation hubs in the world.

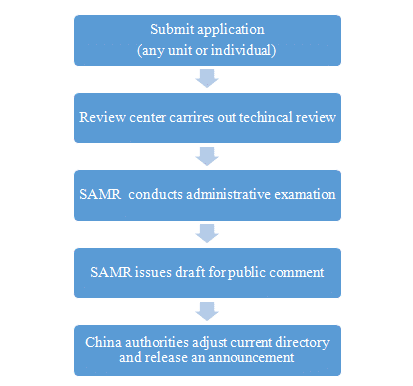

The Health Food and Functional Food market is overseen by the State Administration for Market Supervision (SAMR), which also regulates intellectual property and drug safety. Prior to 2019, only 27 health functions were approved in China, however, SAMR announced that starting in October 2019 any unit or individual can apply for new health function or apply to list new food ingredients [Figure four].

Figure Four. State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) in China.

- To apply for a new health function your application must include: the name of the health function, its mechanism and naming basis, the R&D report of health function, function test reports, function-related materials, and scientific literature.

- To apply for a new raw material your application must include: name, scope of daily intake and corresponding health function, quality standard, functional/characteristic components and detection methods, suitable and unsuitable crowds, reports of adverse reactions in humans, other related materials.

This new measure, which enables your ingredient or health claim to be accepted as a new addition to the Health Food Raw Material Directory and Function Directory, shows a shift in the attitude of the Chinese government – they are signaling their favorable attitude towards the health food market, and desire to become a leader in the space.

In 2019 the Chinese government also adopted a new e-commerce law which places regulations around the marketing and sale of health/ functional foods via the internet. This is notable as it is an aspect of the market that other countries have been slow to regulate.

What does this mean for manufacturers?

Countries have different terms to elucidate dietary supplements, different dosage requirements, and, can even differ in what is considered a supplement versus a medicine. This makes it important for manufacturers and distributors to take the time to understand the guidelines in the country they’re conducting business. Overall, the market trend is towards stricter regulations, however, an increase in regulations can result in consequences, like in Canada, where pre-approval requirements have led to manufacturers complaining about the long wait times before being able to put their products on the market. Thus, there is a need to find a way that isn’t as expensive as pharmaceutical testing but demonstrates the quality and credibility of health products. The most promising way to meet this need is by adopting a screening platform made specifically for nutraceuticals using alternative model organisms.

There are also questions regarding the future of regulations when it comes to selling these products online, as the online marketplace poses the opportunity for people to buy outside of their country and thus, purchase products which do not meet their country’s standards. As the world gets smaller thanks to increased trade and the ability to sell online, we must think about how to adjust the nutraceutical market to fit the needs of all buyers and sellers. This can most easily be done by first creating a standardized definition of what constitutes nutraceuticals/supplements/health foods, and adopting some basic regulations regarding their production and distribution.

References:

- Business Wire (2019). Global Dietary Supplements Market Report 2020. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20210219005385/en/Global-Dietary-Supplements-Market-Report-2020-Market-to-Reach-298.5-Billion-by-2027—U.S.-Market-is-Estimated-at-46-Billion-While-China-is-Forecast-to-Grow-at-12.7-CAGR—ResearchAndMarkets.com

- CRN [Council for Responsible Nutrition] (2020). Dietary Supplement Usage Up Dramatically During Pandemic, New Ipsos-CRN Survey Showshttps://www.crnusa.org/newsroom/dietary-supplement-usage-dramatically-during-pandemic-new-ipsos-crn-survey-shows

- Zayets, V. (2019). Comparing Dietary Supplement Regulations in the U.S. and Abroad. Food and Drug Law Journal, 74(4), 613-629. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27007715

- Fiorito, S. & Livatino J. (2019). Nutraceuticals are on the rise. https://www.beazley.com/beazley_academy/nutraceuticals_are_on_the_rise_and_so_is_the_risk.html

- FDA (2021). Facts About the Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMPs), https://www.fda.gov/drugs/pharmaceutical-quality-resources/facts-about-current-good-manufacturing-practices-cgmps

- Coppens, Patrick (2018). Food Supplements in the European Union: the Difficult Route to Harmonization, RAPS (Regulatory Affairs Professionals Society). https://www.raps.org/news-and-articles/news-articles/2018/7/food-supplements-in-the-european-union-the-diffic

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) (2021). Food Supplements. https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/food-supplements

- Kušar, A., Žmitek, K., Lähteenmäki,L., Raats, M.M., Pravst, I., (2021). Comparison of requirements for using health claims on foods in the European Union, the USA, Canada, and Australia/New Zealand, Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 20(2), 1307-1332. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12716

- CRS Report for Congress, Porter, Donna V. (2005) Dietary Supplements: International Standards and Trade Agreements, report, University of North Texas Libraries, UNT Digital Library, https://digital.library.unt.edu; crediting UNT Libraries Government Documents Department. https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metacrs9110/:

- Thakkar, S., Anklam, E., Xu, A., Ulberth, F., Li, J., Li, B., Hugas, M., Sarma, N., Crerar, S., Swift, S., Hakamatsuka, T., Curtui, V., Yan, W., Geng, X., Slikker, W., & Tong, W. (2020). Regulatory landscape of dietary supplements and herbal medicines from a global perspective. Regulatory toxicology and pharmacology : RTP, 114, 104647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2020.104647