Summary

Turmeric has become a buzzword in the health community, its market size growing immensely in the past few years: approximately doubling from $50.3 million in 2017 to $97 million in 2020, and is expected to continue this growth, jumping to $191.89 million by 2028 (Grand View Research, 2021; Schultz, 2021). But what separates turmeric from other health fads like the routinely debunked ‘celery juice detox’ trend? In this article we dive into the history of turmeric, its current uses, and its potential future applications that could improve overall healthspan as well as target specific debilitating conditions.

A note on safety: as we’ve discussed supplements are currently not overly regulated in the USA – you should always buy a reputable brand, and any medical advice should be discussed with your doctor as supplements can have synergistic or antagonistic effects depending on dosage and any other supplements and medicines you may be taking.

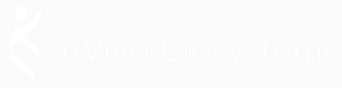

Image 1. Three major cucuminiods in turmeric and their chemical structures (Xu et al., 2018).

Turmeric has been widely used as a spice for centuries, but it is also prominent in traditional medicines as an herb to treat inflammation, pain, wound healing, and digestive distress (Singletary, 2020). In the last few years turmeric has become a prominent supplement in the nutraceutical industry – being added to products such as beverages and processed foods as well as being marketed in pill form. While this boom may be surprising to some, the effort to bring turmeric into mass-produced products, and Western medicine is not new. In fact, as of 2019 there were over 150 preclinical and clinical studies published to examine the health benefits of turmeric on human health.

Insights into Tumeric

While the average person may know of turmeric as the bright orange root, what scientists are actually interested in are the natural polyphenol compounds that are derived from turmeric: curcumin, demethoxycurcumin, and bisdemethoxycurcumin [Figure 1].

Of the three natural polyphenol compounds found in turmeric, most research has focused on curcumin, the compound that gives turmeric its distinctive yellow pigment. These studies have displayed the wisdom of traditional medicines, finding that curcumin is better absorbed when paired with black pepper (increases bioavailability by 2000%) and oil-heavy foods as it is fat-soluble. This being said, there actually is not a lot of curcumin in turmeric, only approximately 3%, which is why many people turn to supplements, or synergistic blends of supplements in order to reap the true benefits of curcumin [Image 2].

![Turmeric has been widely used as a spice for centuries, but it is also prominent in traditional medicines as an herb to treat inflammation, pain, wound healing, and digestive distress (Singletary, 2020). In the last few years tumeric has become a prominent supplement in the nutraceutical industry - being added to products such as beverages and processed foods as well as being marketed in pill form. While this boom may be surprising to some, the effort to bring turmeric into mass-produced products, and Western medicine is not new. In fact, as of 2019 there were over 150 preclinical and clinical studies published to examine the health benefits of turmeric on human health. Insights into Tumeric: While the average person may know of turmeric as the bright orange root, what scientists are actually interested in are the natural polyphenol compounds that are derived from turmeric: curcumin, demethoxycurcumin, and bisdemethoxycurcumin [Figure 1]. Of the three natural polyphenol compounds found in turmeric, most research has focused on curcumin, the compound that gives turmeric its distinctive yellow pigment. These studies have displayed the wisdom of traditional medicines, finding that curcimin is better absorbed when paired with black pepper (increases bioavailability by 2000%) and oil-heavy foods as it is fat-soluble. This being said, there actually is not a lot of curcimin in turmeric, only approximately 3%, which is why many people turn to supplements, or synergistic blends of supplements in order to reap the true benefits of curcimin [Image 2]. Composition of turmeric](https://invivobiosystems.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/tumeric-composition-pie-chart.jpg)

Image 2. Composition of turmeric (C. longa) rhizome (Zhang & Kitts, 2021).

The current state of turmeric and curcumin in pharmaceuticals

Many researchers say that curcumin’s low bioavailability (the proportion of the nutrient that is absorbed in the body) is why it’s rarely used in medical clinics despite studies strongly suggesting turmeric has these anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-aptoisis properties – and, may be able to act as a protective compound against insulin resistance, obesity, and diabetes mellitus.

Another reason for curcumin’s lack of use in western medicinal clinics and mass produced pharmaceuticals, is the uncertainty over curcumin’s mechanism of action (MoA). It is believed that its anti-inflammatory effect is most likely mediated through its ability to inhibit free radicals that cause oxidative damage – while more studies are needed to confirm this, it would make curcumin a particularly powerful, widely applicable therapeutic, as there is growing awareness in how impactful inflammation is in chronic conditions such as heart disease, cancer, metabolic syndrome, Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), and other degenerative diseases. Furthermore, curcumin has been shown to increase BDNF levels (brain-derived neuropathic factor levels). BDNF is a protein that plays a key role in learning and memory – increased levels are associated with improved cognition and low levels are seen in degenerative neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s. Specific studies investigating curcumin’s applicability for certain diseases and disorders are outlined below.

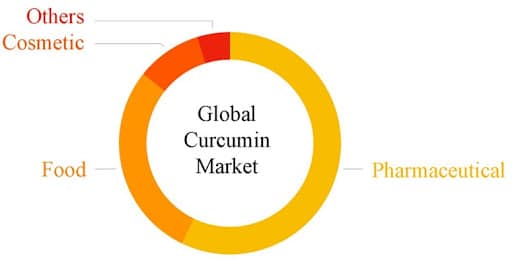

Image 3. Global curcumin market by application (Sharifi-Rad et al., 2020).

In Arthritis

Paultre et al. (2020) analysized 10 studies that compared the effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs such as aspirin and ibuprofen) on people suffering from knee osteoarthritis (OA). In all the studies, the individuals treated with curcumin experienced improvement both in function and their pain levels as opposed to the placebo group. And, three of the studies found that the curcumin treatment had the same effect as the NSAIDs.

In Neurodegenerative Disorders

As previously mentioned, curcumin has been shown to improve or restore BDNF levels which has led researchers to propose their use as a neuroprotective agent. Based on the observation that rates of Alzheimer’s Disease are significantly lower in India as opposed to the USA, Miyasaka et al. (2016) tested the effect of curcumin on tau-induced neuronal dysfunction. First, they developed a transgenic C. elegans which expressed human (R406W) tau. Then, the worms were treated with curcumin. While the curcumin-treatment did not prevent tau-expression, it improved behavioural abnormalities, and increased the level of acetylated α-tubulin – suggesting tubulin may play a critical role in controlling Tau toxicity.

In Depression and Chronic Stress

Curcumin’s neuroprotective effects have also been found to significantly alleviate depression-like behaviours, and inhibit neuronal cell death in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex – a hallmark of depression (Fan et al., 2019). In a small, but remarkable study, 60 people suffering from depression were randomized into three groups: one took a commonly prescribed antidepressant (Prozac), another group took 1 gram of curcumin, and the last group took both. After taking their respective treatments for 6 weeks, the improvement in the curcumin and Prozac groups were comparable, while the group taking both showed the most improvement (Sanmukhani et al., 2014).

People with no pre-existing conditions

There have not been many studies conducted on curcumin’s effect on healthy people, and making cross-comparisons between the studies which do exist is difficult as studies use varying doses – going up to a dose of 1 gram which is considered high as it is unobtainable by simply consuming turmeric root as a part of one’s diet (Hewlings & Kalman, 2017). To better investigate curcumin’s proposed health benefits on people with no pre-existing conditions, DiSilvestro, Joseph, Zhao & Bomer (2012) conducted a low dosage study on healthy adults (40-60 years old). Participants were either given 80mg curcumin or a placebo pill for four weeks: those taking the curcumin had significantly lowered triglyceride levels (a type of fat (lipid) in your blood which raises your risk of heart-disease), and a decrease in salivary amylase activity (an enzyme associated with stress-levels). Furthermore, the curcumin-taking group showed a decrease in beta amyloid plaques, a hallmark in degenerative neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s. Thus, even a low dose of curcumin may provide health benefits for generally healthy individuals.

Curcumin’s future as a therapeutic

With the rise in consumer interest in Turmeric, more companies are developing turmeric-based products – and, thanks to increased regulatory and consumer pressure, more research is going into new delivery approaches that could improve the bioavailability of curcumin, and curcuminoids overall (Singletary, 2020). For example, researchers have tried encapsulating curcuminoids with turmeric essential oils, as they can enhance intestinal permeability. And, looking forwards, there is potential for development of supplements and therapies which incorporate curcumin into micelles, microemulsions, liposomes, nanoparticles, and in other lipid and biopolymer particles (Singletary, 2020). Thus, while the currently available turmeric products may not be ideal, it is an extremely promising ingredient to improve the health and function for people suffering from a range of diseases, as well as generally healthy individuals.

References

- DiSilvestro, R. A., Joseph, E., Zhao, S., & Bomser, J. (2012). Diverse effects of a low dose supplement of lipidated curcumin in healthy middle aged people. Nutrition journal, 11, 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-11-79

- Fan C, Song Q, Wang P, Li Y, Yang M and Yu SY (2019) Neuroprotective Effects of Curcumin on IL-1β-Induced Neuronal Apoptosis and Depression-Like Behaviors Caused by Chronic Stress in Rats. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 12:516. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00516

- Grand View Research (2021). Curcumin Market Worth $191.89 Million By 2028 | CAGR: 16.1%, Grand View Research Press Release, https://www.grandviewresearch.com/press-release/curcumin-market

- Hewlings, S. J., & Kalman, D. S. (2017). Curcumin: A Review of Its Effects on Human Health. Foods (Basel, Switzerland), 6(10), 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods6100092

- Miyasaka, T., Xie, C., Yoshimura, S., Shinzaki, Y., Yoshina, S., Kage-Nakadai, E., Mitani, S., & Ihara, Y. (2016). Curcumin improves tau-induced neuronal dysfunction of nematodes. Neurobiology of aging, 39, 69-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.11.004

- Paultre K, Cade W, Hernandez D, et alTherapeutic effects of turmeric or curcumin extract on pain and function for individuals with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic reviewBMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2021;7:e000935. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000935

- Sanmukhani, J., Satodia, V., Trivedi, J., Patel, T., Tiwari, D., Panchal, B., Goel, A., & Tripathi, C. B. (2014). Efficacy and safety of curcumin in major depressive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Phytotherapy research : PTR, 28(4), 579-585. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.5025

- Sarraf, P., Parohan, M., Javanbakht, M. H., Ranji-Burachaloo, S., & Djalali, M. (2019). Short-term curcumin supplementation enhances serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor in adult men and women: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrition research (New York, N.Y.), 69, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2019.05.001

- Schultz, H. (2021). Once sprightly turmeric market showing signs of maturity, Food Navigator USA, https://www.foodnavigator-usa.com/Article/2021/10/07/Once-sprightly-turmeric-market-showing-signs-of-maturity?utm_source=copyright&utm_medium=OnSite&utm_campaign=copyright

- Sharifi-Rad, J., Rayess, Y. E., Rizk, A. A., Sadaka, C., Zgheib, R., Zam, W., Sestito, S., Rapposelli, S., Neffe-Skocińska, K., Zielińska, D., Salehi, B., Setzer, W. N., Dosoky, N. S., Taheri, Y., El Beyrouthy, M., Martorell, M., Ostrander, E. A., Suleria, H., Cho, W. C., Maroyi, A., … Martins, N. (2020). Turmeric and Its Major Compound Curcumin on Health: Bioactive Effects and Safety Profiles for Food, Pharmaceutical, Biotechnological and Medicinal Applications. Frontiers in pharmacology, 11, 01021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.01021

- Xu, X.-Y., Meng, X., Li, S., Gan, R.-Y., Li, Y., & Li, H.-B. (2018). Bioactivity, Health Benefits, and Related Molecular Mechanisms of Curcumin: Current Progress, Challenges, and Perspectives. Nutrients, 10(10), 1553. MDPI AG. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/nu10101553

- Zhang, H.A., Kitts, D.D. Turmeric and its bioactive constituents trigger cell signaling mechanisms that protect against diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Mol Cell Biochem 476, 3785-3814 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-021-04201-6