Summary

Pets have been shown to improve human health by lowering blood pressure and cortisol levels (a stress-related hormone) (NIH, 2018). But could they also be the solution to our ever-increasingly sterile environments? In this article we will discuss the microbiome, the growing concern over how our air filters, hand sanitizers, and overall cleanliness is impacting the diversity of our guts, and how our pets could help enrich our lives — giving us not just love, but also microbes!

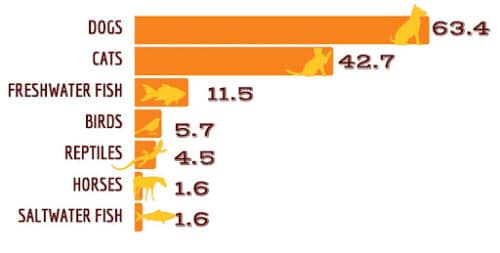

Figure 1. Households in the USA that own pets, in millions (Alt, 2022).

Pets are widely popular in the USA — the numbers differ slightly from survey to survey, but the consensus is that over half of American households have pets, and one recently claimed it is as high as 68% of households (Brulliard & Clement, 2019). When you think about it though, it really isn’t that surprising. Take dogs, for instance, known as man’s best friend, they are regularly taken on vacations, out to restaurants, and into pet-friendly offices. We share our food with them (sometimes even when we’re not supposed to, did any child really eat their peas?) and there is a huge market for pet supplies and accessories. That $123.6 billion market has made it possible for us to match with our pets in nearly every facet of our lives: from outfits to Christmas ornaments (APPA, 2022). There are even pet probiotic products nowadays, piggybacking on the popularity of gut-health products for humans.

Pre, Pro, Post, and Syn- biotic products are dietary supplements that act as targeted therapeutics for restoring the balance of an individual’s microbiome. It has become well-established that a balanced microbiome promotes health, whereas an imbalance in these microbes, or a lack of microbiota diversity, are associated with disease (Durack & Lynch, 2019). Studies have shown that microbiota are transmitted among family and social networks, but what about our furry family members? (Brito et al., 2019). Do we share our microbes with them too? And how does that impact our health?

Sharing is caring: how your pet’s microbes interact with yours

While we love our pets, they engage in activities we’d rather avoid: cats catch mice and walk through litter boxes, while dogs roll in mud and sniff each other’s bottoms. While we might like to avoid thinking about how this tracks into our homes, the research makes it unavoidable. Differences can even be seen in indoor versus outdoor cats.

From a young age the difference in pet owners versus non-pet owners is evident — Tun et al (2017) found that infants who lived in a furry pet household had distinctly different gut microbial composition at 3-4 months of age as compared to infants who were not exposed to pets. The infants that lived in pet-owning households had an increased abundance of Oscillospira and/or Ruminococcus, which are microbes associated with a decreased likelihood of developing childhood obesity and allergic diseases such as asthma and eczema (AAAAI, n.d). This change in microbiome composition was especially prevalent in infants who were delivered via c-section; this is notable as there is debate over the effect of delivery on health, with many studies showing that c-section may increase risk of microbiome-related diseases such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), metabolic diseases, and neurological conditions (Keag, Norman & Stock, 2018).

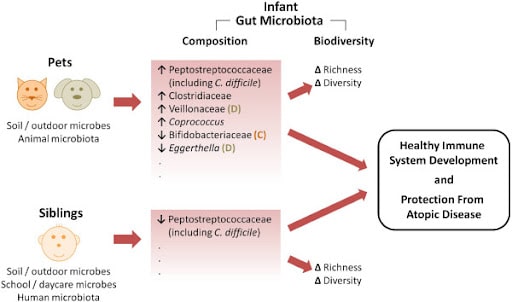

Azad et al. (2013), questioned the validity of these clinical results, however, as their study found that while infants living with pets had richer, more diverse microbiota, infants with siblings had a more simplistic, less diverse composition [Figure 2]. According to the hygiene hypothesis — which states that exposure to early-life infection spurs the development of one’s immune system and protects against allergic disease — this shouldn’t be the case. Rather, exposure to pets and siblings should result in a similar, more diverse microbiota composition. Thus, Azad et al., suggests that their findings may show that microbiota composition is a misleading measure, and that more testing is needed before it should be adopted as an evaluation tool for disease risk and biological mechanisms.

Figure 2. Model for the possible influence of pets and siblings on infant gut microbiota and subsequent development of atopic disease (Azad et al., 2013).

Health Impacts

The hygiene hypothesis has led to concern that our ever-increasingly serialized environments are going to make us more amenable to disease and allergies – meaning we will be sicker in the long term. The explosion of hand sanitizer usage during the COVID-19 pandemic alone is enough to concern clinicians on long-term effects on antimicrobial resistance (Mahmood et al., 2020). This being said, some researchers are turning to pets, and the pet microbes they introduce into our environment, as a potential countermeasure.

Netzin Steklis, a biologist at the University of Arizona, is taking this thought a step further, suggesting that pets may not only support our immune systems, but that the microbes they share with us may act as an antidepressant thanks to the gut-brain axis (Schiffman, 2017).

Conclusion

The microbiome presents an exciting new chapter for personalized medicine — affecting systems as far reaching as the immune system to the brain, therapeutics designed to alter microbiome composition may be able to improve nearly every human disease. But there are many ways of impacting our microbial composition, and, as humans progress more and more into a sterilized, urban-lifestyle, it will be vital to look at the aspects of our environments which are easily overlooked, for instance, our pets.

References

- NIH (2018). The Power of Pets. NIH, News in Health. https://newsinhealth.nih.gov/2018/02/power-pets#:~:text=Interacting%20with%20animals%20has%20been,support%2C%20and%20boost%20your%20mood.

- Schiffman, R. (2017). Are Pets the New Probiotic? The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/06/well/family/are-pets-the-new-probiotic.html

- Kates, A. E., Jarrett, O., Skarlupka, J. H., Sethi, A., Duster, M., Watson, L., Suen, G., Poulsen, K., & Safdar, N. (2020). Household Pet Ownership and the Microbial Diversity of the Human Gut Microbiota. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology, 10, 73. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2020.00073

- Alt, K. (2022). Pet Ownership Statistics: How Many Dogs Are In The World? CanineJournal, https://www.caninejournal.com/pet-ownership-statistics/

- Brulliard, K. & Clement, S. (2019). How many Americans have pets? An investigation of fuzzy statistics. The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/science/2019/01/31/how-many-americans-have-pets-an-investigation-into-fuzzy-statistics/

- Brito, I.L., Gurry, T., Zhao, S. et al. Transmission of human-associated microbiota along family and social networks. Nat Microbiol 4, 964–971 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-019-0409-6

- APPA (2022). Pet Industry Market Size, Trends & Ownership Statistics. APPA. American Pet Products Association. https://www.americanpetproducts.org/press_industrytrends.asp

- Durack J, Lynch SV. (2019) The gut microbiome: Relationships with disease and opportunities for therapy. J Exp Med. ;216: 20–40

- Tun, H. M., Konya, T., Takaro, T. K., Brook, J. R., Chari, R., Field, C. J., Guttman, D. S., Becker, A. B., Mandhane, P. J., Turvey, S. E., Subbarao, P., Sears, M. R., Scott, J. A., Kozyrskyj, A. L., & CHILD Study Investigators (2017). Exposure to household furry pets influences the gut microbiota of infant at 3-4 months following various birth scenarios. Microbiome, 5(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-017-0254-x

- AAAAI (n.d.). Atopy. https://www.aaaai.org/Tools-for-the-Public

- Keag OE, Norman JE, Stock SJ.( 2018) Long-term risks and benefits associated with cesarean delivery for mother, baby, and subsequent pregnancies: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. ;15: e1002494.

- Azad, M. B., Konya, T., Maughan, H., Guttman, D. S., Field, C. J., Sears, M. R., Becker, A. B., Scott, J. A., & Kozyrskyj, A. L. (2013). Infant gut microbiota and the hygiene hypothesis of allergic disease: impact of household pets and siblings on microbiota composition and diversity. Allergy, asthma, and clinical immunology : official journal of the Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 9(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1710-1492-9-15

- Mahmood, A., Eqan, M., Pervez, S., Alghamdi, H. A., Tabinda, A. B., Yasar, A., Brindhadevi, K., & Pugazhendhi, A. (2020). COVID-19 and frequent use of hand sanitizers; human health and environmental hazards by exposure pathways. The Science of the total environment, 742, 140561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140561

- Schiffman, R. (2017). Are Pets the New Probiotic?, The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/06/well/family/are-pets-the-new-probiotic.html