Summary:

Since 1938, the FDA has required potential drugs to be tested for safety and efficacy in animals before moving to human clinical trials. Historically, this has meant that every therapeutic intervention must be tested in a rodent model (mouse or rat) and one nonrodent species (dog or monkey). Recently, however, the FDA announced legislative changes that make animal testing no longer necessary. So what does this mean for drug discovery? Will the drug pipeline be faster? Just as safe? In this article we will discuss the new law, and its implications for the future of America’s drug pipeline.

On December 29th 2022, President Biden signed into law the FDA Modernization Act 2.0 which saw bipartisan support and was unanimously passed in the Senate. The aim of this legislation is to “accelerate innovation and get safer, more effective drugs to market more quickly by cutting red tape that is not supported by current science” (Paul, 2023). To this end, the new FDA legislation removes the mandate which requires drug therapeutics to be tested on animals before moving onto human clinical trials.

While animal welfare groups are praising this move, saying that it will not only save thousands of animals from unnecessary suffering, but will also make drug screening “faster, better, and more efficient”, what will the real effect of this law be? (Paul, 2023).

The Need for the New Law

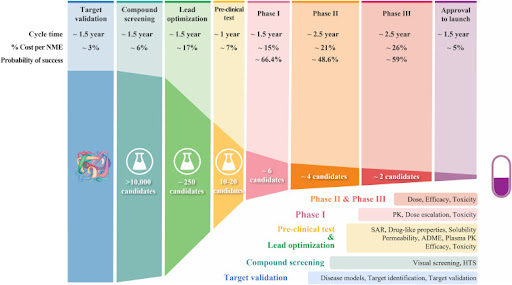

Traditionally, drug development has been an expensive and lengthy process, taking 7-10 years and costing hundreds of millions of dollars. One of the reasons why the drug development pipeline is so time consuming, is that, previously, the U.S. Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act required drug developers to test potential drug therapeutics in a rodent (mouse or rat) model and one nonrodent species model (dog or monkey) before moving into the human clinical trial phase (Hernandez, 2023).

Despite the intended effect of this stipulation, that drugs will be safer, and more effective by the time they are tested in humans, this has not been the case. In fact, more than nine in 10 drugs fail in human clinical trials, thus, many researchers and animal welfare organizations argue that animals are not a good indicator of drug viability (Sun, Gao, Hu & Zhou, 2022).

I don’t think the organ-on-chip will do it all. I think we’ll need a battery of different, complementary tests

Professor Jeffrey Morgan, director of the Center for Alternatives to Animals in Testing at Brown University

Figure 1. The process of drug discovery and development, and the failure rate at each step (Sun, Gao, Hu & Zhou, 2022).

Furthermore, as we’ve discussed in previous blogs, the outbreak of COVID-19 has had broad, long-lasting impacts on biomedical research. The sudden need to shut down labs meant that masses of laboratory animals had to be euthanized, and, as many of these animals are specific lines raised by their researchers to fit a particular need, this setback research by years. Once labs were back up and running, another issue came into play: animal shortages. Before the pandemic the USA imported over 60% of research from China (Zhang, 2020). This also led to delays in research, and made many researchers look to other, alternative models for their research. For instance, Christian Lawrence, Assistant Director of Research Operations at Boston Children’s Hospital, said that the COVID-19 pandemic really “highlights one of the strengths of the zebrafish model system,” as this vertebrate model requires less oversight and fewer resources than a mammalian rodent model.

Thus, taken together, these factors point to a clear need for something in the drug development process to change. But is this legislative change, removing the need for animal testing altogether, the right move?

The New Law’s Impact

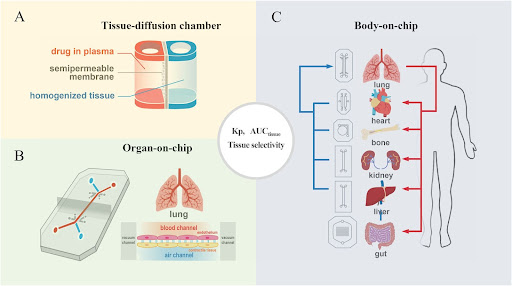

First, it is important to note that the bill doesn’t ban animal testing outright but enables drug developers to use alternative methods where they are suitable; these alternative methods include computer modeling and Organs-on-chips (OoCs), which are systems containing tissues (either engineered or natural) grown inside microfluidic chips.

Recently, the potential benefit of technologies such as liver chips were displayed when the biotech Emulate published a study showing that their company’s chips were able to accurately predict 87% of a variety of on-the-market drugs which were originally tested in animals (Ewart et al., 2022). Lorna Ewart, the chief scientific officer of biotech Emulate explains how alternatives such as organs-on-chips may prove to be better models than animals as, “animal models may not be accurate predictors of liver toxicities for people, because animals metabolize drugs differently than humans do” (Mullin, 2023).

Figure 2. Alternative drug screening tools: (A) Tissue diffusion chamber may provide an easy and high throughput screening to study structure‒tissue exposure/selectivity relationship (STR). (B) Single-organ chips, and (C) Body-on-a-Chip integrates multiple organ units to study STR in different organs (Sun, Gao, Hu & Zhou, 2022.)

This being said, organs-on-chips have limitations, for instance, they are only able to model various organ-specific functions. Notably, this makes OoCs inapplicable to studying the nervous system, which is one area of drug discovery which suffers the most from high drug discovery failure rate.

More than nine in 10 drugs that enter human clinical trials fail

Wadman, 2023

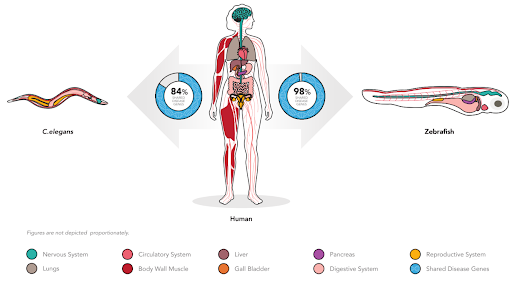

One mid-route option is for drug developers to opt for alternative model organisms, for instance, the zebrafish and small nematode, C. elegans. , Both animal models boast the benefit of enabling in vivo testing, and high homology with humans while being much lower cost than a mammalian model, and having an accelerated study timeline. [Figure 3].

Figure 3. Shared disease genes between humans, and the alternative animal models C. elegans and zebrafish.

We can make these animals even more relevant with Whole-gene Humanized Animal Models (WHAM) platform technology. We replace the animals coding sequence with human coding sequence and the resulting human protein can now rescue and retain function of the animal’s version of the gene. The WHAM-humanized animal model will be much less prone to the false discovery (false positives and false negatives) that have plagued other animal models in the past.

As a contract research organization (CRO), InVivo Biosystems collaborates with researchers and drug developers to test the safety and efficacy of compounds utilizing the alternative model organisms. Zebrafish and C. elegans are both well-established models for biomedical research, and drug discovery in particular. For instance, InVivo Biosystems has had resounding success utilizing these organisms to develop rare disease therapeutics.

Conclusion:

While the new FDA Modernization Act 2.0 is exciting as it shows progress in how the USA’s legislators are thinking about biomedical research, and a revitalized effort to improve the drug discovery process, people should not misconstrue this new legislative announcement as a complete shift away from animal models in research. As many researchers have noted, animal models will probably always exist in science, however, in an effort to advance our understanding of the mechanisms behind diseases we need to employ all of the tools at our disposal, including new technologies and the combination of multiple methods.

References:

- Wadman, M (2023). FDA no longer needs to require animal tests before human drug trials, Science, Vol 379, 6628, https://www.science.org/content/article/fda-no-longer-needs-require-animal-tests-human-drug-trials#.Y76rZYPSO3g.twitter

- Paul, S. (2023). Dr. Paul’s Bipartisan FDA Modernization Act 2.0 to End Animal Testing Mandates Included in 2022 Year-end Legislation, Dr Rand Paul, US Senator, Kentucky. https://www.paul.senate.gov/news/dr-pauls-bipartisan-fda-modernization-act-20-end-animal-testing-mandates-included-2022-year

- Hernandez, J. (2023). The FDA no longer requires all drugs to be tested on animals before human trials. Npr, https://www.npr.org/2023/01/12/1148529799/fda-animal-testing-pharmaceuticals-drug-development#:~:text=Press-,FDA%20no%20longer%20requires%20all%20drugs%20to%20be%20tested%20on,that%20don’t%20involve%20animals.

- Zhang, Sarah (2020). America Is Running Low on a Crucial Resource for COVID-19 Vaccines: The country is facing a monkey shortage. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2020/08/america-facing-monkey-shortage/615799/

- Sun, D., Gao, W., Hu, H., & Zhou, S. (2022). Why 90% of clinical drug development fails and how to improve it?. Acta pharmaceutica Sinica. B, 12(7), 3049–3062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2022.02.002

- Ewart, L., Apostolou, A., Briggs, S.A. et al. Performance assessment and economic analysis of a human Liver-Chip for predictive toxicology. Commun Med 2, 154 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43856-022-00209-1

- Weintraub, K. (2022). Animal testing no longer required for drug approval. But high-tech substitutes aren’t ready. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2023/01/15/fda-animal-testing-requirement-lifted-alternatives/10998886002/

- Mullin, E. (2023). The US Just Greenlit High-Tech Alternatives to Animal Testing. WIRED. https://www.wired.com/story/the-us-just-greenlit-high-tech-alternatives-to-animal-testing/

Make a leap forward in drug discovery. Contact us now to unlock the possibilities of our comprehensive drug discovery and development services and expedite the development of life-saving treatments.