Summary

A common saying in science is that, “good science and good animal welfare go hand in hand.” In this article we provide an overview of the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction and Refinement: guiding principles for the humane use of animals in research), look specifically at the UK’s well-documented implementation of them, and discuss how new techniques and technologies can continue to improve animal welfare.

No one, researchers and general public alike, wants to see the unethical treatment of animals. However, model organisms are essential to experimental research as they provide a safeguard before human trials. So, the question becomes, how do we balance the needs of animals and science? In 1959 Russell and Burch sought to answer this question by proposing the 3Rs as guidelines for ethical animal research:

- Replacement: avoid the use of animals in research

- Reduction: use fewer animals, or obtain more information from the same number of animals

- Refinement: improve animal welfare by using methods such as in vivo technologies

These guidelines have been incorporated around the world as laws , such as the Animal Welfare Act, which was passed in the USA in 1966 (USDA, 2021). This legislation protects mammals, however, the Animal Welfare Act, and many others worldwide, do not include rats, mice or birds. Of the countries which have created legislation around the 3Rs, Britain has enacted some of the most stringent guidelines, regulating any living vertebrae other than cephalopod, and requiring researchers to report their use of animals to the Home Office. The Home Office keeps track of these scientific procedures, and publishes a report annually which can be publicly accessed (UK Gov., 2021).

While the UK’s transparency surrounding animal usage is a step in the right direction, the 3Rs’ approach has faced some criticism, and questions as to whether it does enough to ensure the humane use of animals in research.

Criticism of the 3Rs:

Some researchers are wary of unintended consequences that the 3Rs could cause, for instance, by limiting the number of animals used in experiments, proportionally, the animals which are used may be subjected to more tests (more suffering to fewer animals). It has also been suggested that the current legislation of the 3Rs overlooks certain animals (this varies by country) in a way that Russell and Burch did not intend, and that the guidelines themselves are too vague. As a result, these well-meaning principles do not actually have much of an effect. To help make these guidelines stronger, it has been suggested that an additional 3Rs should be added: Robustness, Registration, and Reporting. These proposed Rs would emphasize accountability and transparency (Strech, 2019).

How is the UK doing?

The UK has addressed the criticism that the 3Rs lack accountability and transparency by collecting and reporting their animal data, so, what do their numbers show?

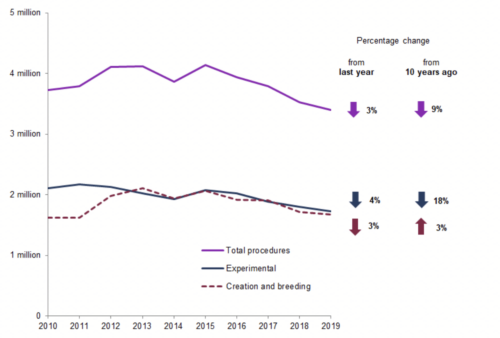

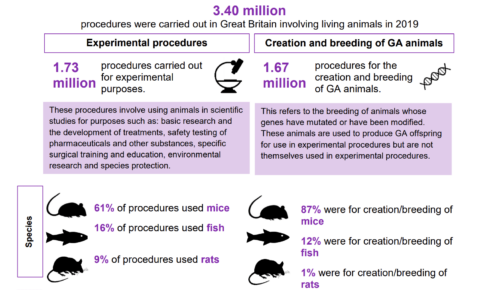

Figure One: Total scientific procedures by type, 2010-2019 (Home Office, 2019).

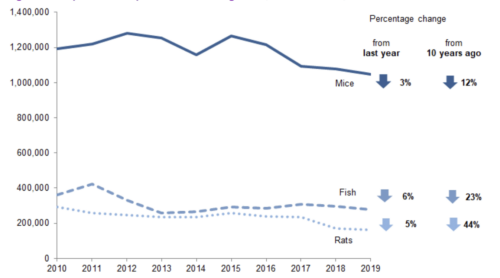

Figure Two: Experimental procedures using mice, fish, and rats 2010-2019 (Home Office, 2019).

Figure Three: Summary statistics for scientific procedures carried out in the UK in 2019 (Home Office, 2019).

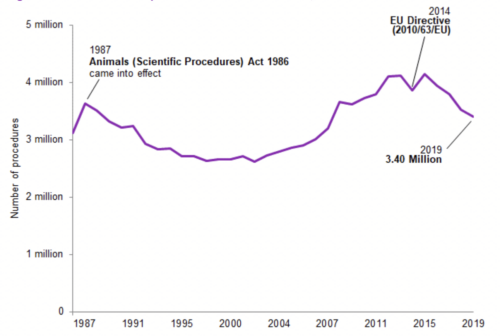

As depicted in the figures above, 2019 showed an overall trend of less animals being used in scientific procedures in the UK (invertebrates are not included in this data, so it is hard to track those numbers). This indicates that despite criticisms of the vagueness of the 3Rs guidelines, their implementation has shown success in the reduced usage of animals.

The figures also show that the creation and breeding of genetically modified animals for research purposes has become more and more prominent since 1998 (largely taking place in mice or fish models) (Figure four). The introduction of transgenic animals has been considered the catalyst for the largest increase in animal usage since the 3Rs were introduced. And so, these 2019 numbers, with their downwards trend in the usage of vertebrate animal models, show a significant improvement in the research’s field’s ability to refine the technology of transgenics over the last two decades.

Figure Four: Total scientific procedures in Great Britain, 1986 – 2019 (Home Office, 2019).

When animal usage increased in the years between 1998 and 2009, it was decided that researchers needed to reassess how to incorporate the 3Rs into research with the new tool of transgenic animals. This resulted in a 2009 workshop held by the Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR) in Berlin, Germany. Experts from Germany and across Europe met with the goal of evaluating the value of transgenic animal models, and finding ways to promote the 3Rs when using transgenic animals (Kretlow et al., 2010).

After the workshop concluded a report was published which laid out the methods they discussed for reduce, refine, or replace transgenic vertebrate experiments:

- Reduce: this report called for laboratory maintenance protocols to be better defined and standardized. It also emphasized the importance of having a well-trained staff, as this can lead to a reduction in the numbers of animals needed for each experiment, and minimize the amount of distress the animals are exposed to. Furthermore, this report noted that open access databases where results of completed experiments can be found (both experiments that had significant findings, and those with ‘negative’ outcomes) would greatly reduce the amount of experiments that need to be replicated worldwide. Since the publication of this study, open access databases have been established, and it has helped lead to a more collaborative scientific community.

- Refine: this report stated that, at the time, the generation of transgenic animals often required a large number of animals/embryos. They predicted that the continued development of transgenic technologies would refine these methodologies, and allow for more data to be collected from fewer animal models. This has certainly been the case with the adoption of methods such as CRISPR-Cas9, which has made it easier to target and activate or silence specific genes.

- Replace: the report identified promising alternative organisms such as the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster and the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans to help minimize the use of mammalian models in research. More simplistic alternatives, like Cell cultures and 3D tissue models, were also proposed as future models. Thus, this report promoted more emphasis on using and developing non-mammalian organisms.

What is the best way forward in 2021?

- Adopt lower organism models. This is often referred to as ‘partial replacement’ as many researchers are finding ways to combine traditional animal models with non-mammalian models. Together, these models can not only fulfill the 3Rs, but often expedite the timeline of research.

- Greater use of non-animal models such as cells and tissue cultures, and computer models. Referred to as ‘full replacement’ these models are becoming increasingly useful, as technologies advance. For instance, the recently developed method, NanoSeq, makes it possible to study how genetic changes occur in human tissues with unprecedented accuracy.

- Continually discuss ways to better implement and track the use of the 3Rs. For instance, a 2009 review of published biomedical research found that there was sporadic use and reporting of the 3Rs. This resulted in not only more animal usage than necessary, but also higher costs, and ‘less good science’, i.e., lower scientific validity (Kilkenny et al., 2009).

In response to this review, the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines were developed (Kilkenny et al., 2010). Many journals now require study directly address the ARRIVE guidelines prior to publication, a step towards the adoption of Stretch’s additional 3Rs (Robustness, Registration, and Reporting).

Conclusion

On an individual lab level, one of the most impactful changes you can make to improve animal welfare is by adopting the partial-replacement approach to research. If you aren’t sure where to start InVivo Biosystems is here to help – as providers of alternate models we’ve successfully delivered 2,500 C. elegans transgenic lines, and also offer zebrafish genome editing services from a team with over 40 years of combined experience. We work with you and your research to create a customized plan to make our collaboration as smooth and fruitful as possible, because what is good for animal welfare is good for science.

References

- Home Office (2019). The Annual Statistics of Scientific Procedures on Living Animals, Great Britain 2019. https://speakingofresearch.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/annual-statistics-of-scientific-procedures-on-living-animals-great-britain-2019.pdf

- Kilkenny, C., Browne, W. J., Cuthill, I. C., Emerson, M., & Altman, D. G. (2010). Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS biology, 8(6), e1000412. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1000412

- Kilkenny, C., Parsons, N., Kadyszewski, E., Festing, M. F., Cuthill, I. C., Fry, D., Hutton, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Survey of the quality of experimental design, statistical analysis and reporting of research using animals. PloS one, 4(11), e7824. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0007824

- Kretlow, A., Butzke, D., Goetz, M. E., Grune, B., Halder, M., Henkler, F., Liebsch, M., Nobiling, R., Oelgeschlaeger, M., Reifenberg, K., Schaefer, B., Seiler, A., & Luch, A. (2010). Implementation and enforcement of the 3Rs principle in the field of transgenic animals used for scientific purposes. Report and recommendations of the BfR expert workshop, May 18-20, 2009, Berlin, Germany. ALTEX, 27(2), 117-134.

- Russell WMS, Burch RL. 1959. (as reprinted 1992). The principles of humane experimental technique. Wheathampstead (UK): Universities Federation for Animal Welfare. http://117.239.25.194:7000/jspui/bitstream/123456789/1342/1/PRILIMINERY%20%20AND%20%20CONTENTS.pdf

- Strech D, Dirnagl U. (2019). 3Rs missing: animal research without scientific value is unethical. BMJ Open Science; 3:bmjos-2018-000048. doi: 10.1136/bmjos-2018-000048

- The Home Office of revised enacted UK legislation 1276-present. (2021). Animal Welfare. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/primary+secondary?title=animal%20welfare

- USDA, National Agricultural Library (2021). Animal Welfare Act. https://www.nal.usda.gov/awic/animal-welfare-act